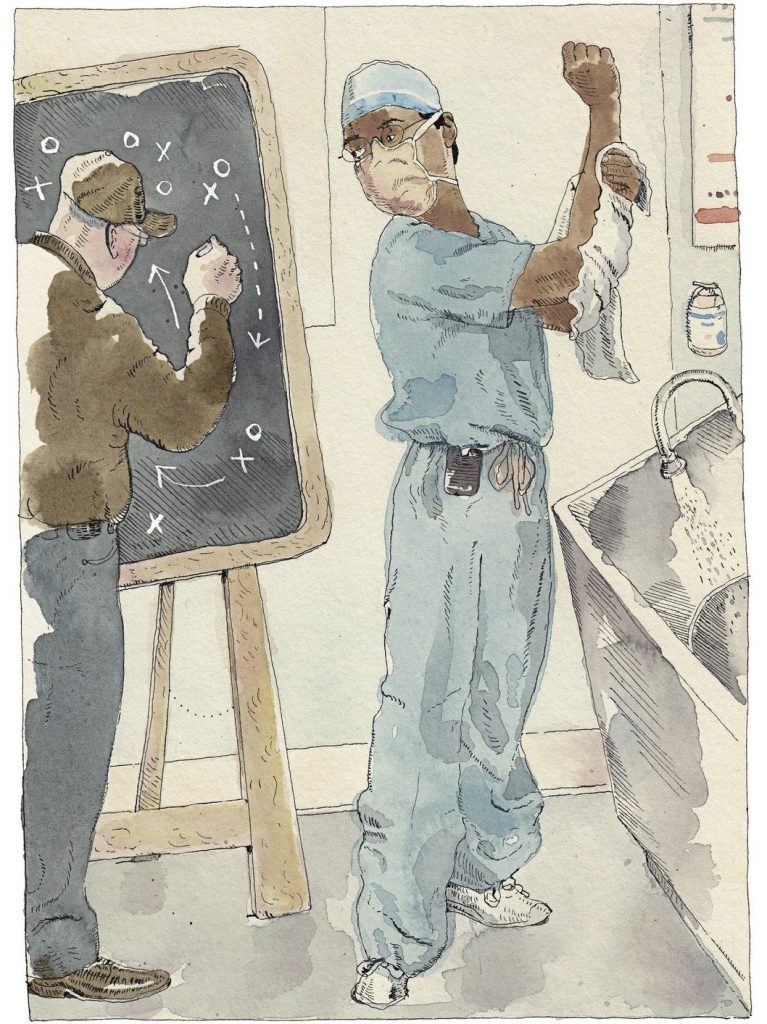

The Coach In The Operating Room

A mentor plays a crucial role in Empowerment and continued improvement

Adapted from an article written by Surgeon Atul Gawande

newyorker.com/magazine/2011/10/03/personal-best

I’ve been a surgeon for eight years. For the past couple of them, my performance in the operating room has reached a plateau. I’d

like to think it’s a good thing—I’ve arrived at my professional peak.

But mainly it seems as if I’ve just stopped getting better. And if I

don’t get better, I can only get worse.

I decided to try a coach. Athletes and musicians have coaches,

why can’t I? I called Robert Osteen, a retired general surgeon, whom I trained under during my residency, to see if he might

consider the idea. He’s one of the surgeons I most hoped to emulate in my career. His operations were swift without seeming hurried and elegant without seeming showy. He was calm. I never once saw him lose his temper. He had a plan for every circumstance. He had impeccable judgment. And his patients had unusually few complications.

Osteen came to my operating room one morning and stood silently observing from a step stool set back a few feet from the table. He scribbled on a notepad and changed position once in a while, looking over the anesthesia drape or watching from behind me. I was initially self-conscious about being observed by my former teacher. But I was doing an operation—a thyroidectomy for a patient with a cancerous nodule— that I had done around a thousand times, more times than I’ve been to the movies. I was quickly absorbed in the flow of it— the symphony of coordinated movement between me and my surgical assistant, a senior resident, across the table from me, and the surgical technician to my side.

The case went beautifully. The cancer had not spread beyond the thyroid, and, in eighty-six minutes, we removed the fleshy, butterfly-shaped organ, carefully detaching it from the trachea and from the nerves to the vocal cords. Osteen had rarely done this operation when he was practicing, and I wondered whether he would find anything useful to tell me.

We sat in the surgeon’s lounge afterward. He saw only small things, he said, but, if I were trying to keep a problem from happening even once in my next hundred operations, it’s the small things I had to worry about.

He noticed that I’d positioned and draped the patient perfectly for me, standing on the patient’s left side, but not for anyone else. The draping hemmed in the surgical assistant across the table on the patient’s right side, restricting his left arm, and hampering his ability to pull the wound upward. At one point in the operation, we found ourselves struggling to see up high enough in the neck on that side. The draping also pushed the medical student off to the surgical assistant’s right, where he couldn’t help at all. I should have made more room to the left, which would have allowed the student to hold the retractor and freed the surgical assistant’s left hand.

Osteen also asked me to pay more attention to my elbows. At various points during the operation, he observed, my right elbow rose to the level of my shoulder, on occasion higher. “You cannot achieve precision with your elbow in the air,” he said.

He had a whole list of observations like this. His notepad was dense with small print. I operate with magnifying loupes and wasn’t aware how much this restricted my peripheral vision. I never noticed, for example, that at one point the patient had blood-pressure problems, which the anesthesiologist was monitoring. Nor did I realize that, for about half an hour, the operating light drifted out of the wound; I was operating with light from reflected surfaces. Osteen pointed out that the instruments I’d chosen for holding the incision open had got tangled up, wasting time.

That one twenty-minute discussion gave me more to consider and work on than I’d had in the past five years.

“Provide yourself with a master.”

ETHICS OF OUR FATHERS